The stated legislative objectives of the prostitution laws that the Canadian Supreme Court recently struck down in Bedford v. Canada were the prevention of public nuisances and the exploitation of prostitutes. However, upon closer examination of the history of these laws, their real objectives become transparent. Canada’s anti-prostitution laws were really there to protect society’s whiteness/maleness. As such, these laws were disproportionately applied to racialized and indigenized bodies. Thus, to understand what the Bedford decision means for Indigenous sex workers is to understand the essence of colonialism and the history of Canada’s anti-prostitution laws.

On December 20, 2013, Canada’s Supreme Court found the following laws relating to prostitution unconstitutional:

- the bawdy house offense, (which prohibits keeping and being an inmate of or found in a bawdy house);

- the living on the avails offense (which prohibits living in whole or in part on the earnings of prostitutes); and

- the communicating offense (which prohibits communicating in a public place for the purpose of engaging in prostitution or obtaining the sexual services of a prostitute). 1

Black Marxist scholar Frantz Fanon best defines colonialism in his seminal work Wretched of the Earth. Fanon writes that “[t]he colonized world is a world divided in two” and that colonialism “is the entire conquest of land and people.” In other words, colonialism is the complete domination and exploitation of Indigenous lands, bodies and identities (and not the fun kind of domination). When colonialism is incorporated into this discussion, the racial undertones within the laws, their application, and objectives are revealed.

The history of the bawdy house law leads directly back to the oppression of Indigenous people. During the Confederation of Canada, in which the British colonies were united, one key piece of legislation was enacted. This was the Indian Act (1867) and its aim was to “get rid of the Indian problem.”2 Along with this enactment, the North West Mounted Police (NWMP) was created (1873). Shortly following the enactment of the Indian Act, offenses relating to prostitution were added to the same legislation. Specifically, the first sections relating to prostitution, written in 1879, included sections banning “houses of prostitution” (or in a contemporary context, “bawdy houses”).

Initially, “houses of prostitution” were defined as being disorderly, a definition which had almost nothing to do with sexual behaviors. These sections also explicitly included wigwams—that is, Indigenous peoples’ houses—meaning that Indigenous houses were assumed to be disorderly by nature. This gave government and policing agencies the permission to enter Indigenous people’s houses on spurious grounds unrelated to the actual offense in question. These same claims that Indigenous houses were disorderly also led to the removal of Indigenous children from their homes, forcing them to attend residential schools designed to erase Indigenous identities from society. Following this, several other sections were included, but were later repealed and replaced in 1880 and 1884. Even though these sections were repeatedly repealed and replaced, changes to prostitution laws always increased the force and effect of these laws on Indigenous women’s bodies. Because these laws originated under the Indian Act, there were no attempts to criminalize non-Indigenous men for similar offenses. Also, the NWMP later amalgamated with the Dominion police, who policed the eastern shores of Canada, to form the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) in 1920. The aims of these policing agencies were also to assist in Canada’s colonial agenda—to get rid of the Indian problem.

By 1892, Canada had enacted its Criminal Code of Canada (CCC), and all offenses relating to prostitution were removed from the Indian Act and placed in the CCC. The enactment of the CCC did not mean that Indigenous bodies were not being actively policed anymore. It contributed to an increased level of policing and violence, because along with the enactment of the Criminal Code of Canada came the establishment of federal institutions (i.e., prisons, residential schools, and mental hospitals) to house Indigenous bodies away from their homes and lands. Indigenous populations don’t make up more than a quarter of the total prison population today for nothing.

The communication and living off of the avails laws’ connection to colonialism becomes evident when we examine how they are disproportionately applied to certain bodies. While all three laws were enacted to prevent public nuisances, the communication law is one of the most aggressive laws ever designed to prevent such a thing. The objective of the communication law was to protect communities from prostitution and prevent prostitutes from safely negotiating the boundaries and terms of a date in a public place, which contradicts one of the initial objectives of these laws, to prevent the exploitation of prostitutes.

Further, given that the communication law targeted individuals who were most visible, like racialized and Indigenous people, especially those who either live or work on the streets, it continued the colonial effort of policing certain types of bodies. Policing certain bodies in public spaces is a direct attempt at maintaining society’s whiteness and maleness. This is not to say that marginalized sex workers who are from a European background did not experience violence as a result of the communication law. The violent effects of policing, however, are more often experienced among those who come from racial and Indigenous backgrounds.

As for the living off the avails law, this law assumes that all relationships in a sex worker’s life are exploitative.3 This assumption is harmful, especially to Indigenous women, because it alienates and marginalizes sex workers. To further complicate the situation, Canadian policing agencies assume that perpetrators are from the same ethnic background as victims. That is to say that if a sex working Indigenous woman is living with a boyfriend of the same racial background, the police will assume that this personal relationship is exploitative in nature. What are Canadian policing agencies really trying to accomplish with these types of discourses? Indigenous scholar Lee Maracle said it best in her book I Am A Woman when she explained that the aims of the colonizer are “to break up communities and families, and destroy a sense of nationhood.”

Bedford marks a victory in the struggle against colonialism and colonial structures for Indigenous sex workers. When we begin to understand the history of Canada’s anti-prostitution laws, and the policing of Indigenous bodies and identities, we understand how the construction of these identities and bodies serve to sustain colonialism and all its tools. The criminalization of the sex trade is the criminalization of certain bodies and identities, because we all know that it isn’t white men who get arrested for prostitution related crimes on a daily basis. In the end, decriminalization of the trade is decolonization of the trade, and thus the Bedford v. Canada decision is a step toward decolonization.

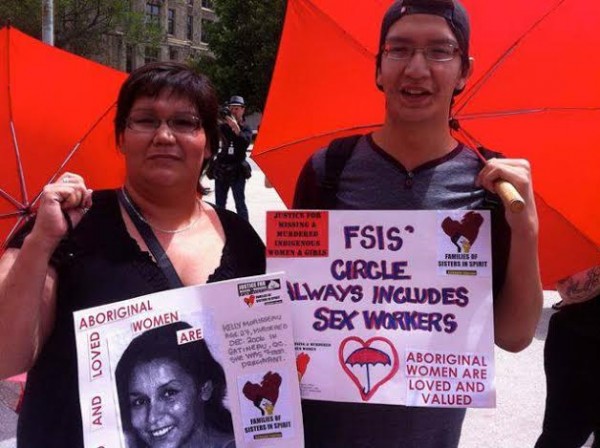

If you are interested in organizations that work with Indigenous sex workers, Families of Sisters in Spirit (FSIS) is a grassroots not-for-profit volunteer organization located on unceded Algonquin Territory (Ottawa) led by families of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, including Indigenous sex workers, with support from Indigenous and non- Indigenous allies. FSIS supports the decriminalization of the sex trade. If you would like to contribute to FSIS in their fight for justice for missing and murdered Indigenous women in Canada, please visit http://

1. http://www.pivotlegal.org/canada_v_bedford_a_synopsis_of_the_supreme_court_of_canada_ruling ↩

2. http://www.danielnpaul.com/IndianResidentialSchools.html ↩

3. As outlined in Bedford v. Canada decision paragraph 67 ↩

Awesome!

Wooo! Awesome piece Naomi.

[…] Read more at “Prostitution Laws: Protecting Canada’s Crackers Since 1867″ […]

WOW. This perspective is also echoed in Thaddeus Russell’s detailed account of what has happened historically in the USA regarding such laws. What we have now is a more GLOBALIZED effort.

I have asked myself, could anti prostitution efforts (referred to as anti human slavery efforts) be a sneaky strategy to further establish a global governing/controlling system? Accomplished under the guise of rescuing people and with no one paying attention because they think it will only impact sex workers and traffickers? It’s already happening, but in the end it will have far reaching effects well beyond the sex industry, and gives various government agencies far reaching control beyond what they already have. Look at the agencies involved. The FBI, Homeland Security, the DHS, well beyond local law enforcement. Read Thaddeus Russell’s article Sex slavery and the surveillance state if you don’t get where I am going here. When you realize that in its infancy, the FBI gained an incredible amount of power via the past human trafficking hysteria, and was practically born out of this hysteria, it makes more sense. They have been doing this shit for years and they are just getting BETTER at it.

All roads lead to Rome.