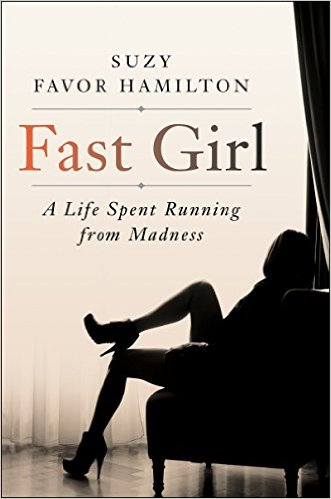

Suzy Favor Hamilton’s autobiography, Fast Girl: A Life Spent Running From Madness, catalogs the Olympic runner’s experience with mental illness, her career shift from professional mid-distance running to high-end escorting, and her eventual outing and diagnosis as bipolar. Following the birth of her daughter and her retirement from running, Favor Hamilton found her career path fraught and unsatisfactory, its travails amplified by her growing problems with postpartum depression and bipolar. Eventually, the media outed her as a sex worker, exacerbating her struggles.

Suzy Favor Hamilton’s autobiography, Fast Girl: A Life Spent Running From Madness, catalogs the Olympic runner’s experience with mental illness, her career shift from professional mid-distance running to high-end escorting, and her eventual outing and diagnosis as bipolar. Following the birth of her daughter and her retirement from running, Favor Hamilton found her career path fraught and unsatisfactory, its travails amplified by her growing problems with postpartum depression and bipolar. Eventually, the media outed her as a sex worker, exacerbating her struggles.

From growing up picked on by her bipolar brother in small town Wisconsin, to her love/hate relationship with the athletic talent she built into a career, and the way that relationship shaped her psyche and primed her for sex work, Fast Girl covers a wide range of material. It is also one of the more honest memoirs I’ve seen on the day-to-day struggle of being bipolar, and how the disorder can escalate.

I’ve been diagnosed with bipolar disorder and other mental illnesses. My thoughts upon reading the book were filtered through my own experiences with the illness: some of these ideas may seem strange if you haven’t lived with bipolar disorder, or lived with someone who copes with it.

In my experience, an important thing to understand about living with bipolar disorder is that it doesn’t always make sense to those who don’t suffer from the disease. Triggers might be minor, like someone looking at you wrong. You might never find out exactly what association triggered your most recent bipolar episode. Sometimes you do know exactly what the trigger is, but even when you know, you can’t really stop it, only remind yourself your perceptions aren’t reflecting reality.

At times, bipolar made my work in a strip club a hell in which I was irrationally afraid of accepting drinks, terrified that every customer was laughing at me. It made me second guess every moment so thoroughly that suicide sometimes felt like a logical post-shift endeavor. At its worst, this illness makes me question everything about myself: my agency, my sanity, my humanity, my very perceptions. My body and mind became communal property- things for others to manage without my input, sometimes overriding my preferences.

Accepting treatment for a mental illness like bipolar can feel like a violation to me. I have to accept that it’s not about me, it’s about what people around me want for me. Maybe I want it, too, but accepting that treatment means accepting I won’t be the arbiter of what’s “right” for myself. That is left to the family members who can no longer handle my outbursts, or the doctor who thinks that no matter how I feel now, it’s worth reaching for something even better by shifting the med dosages, even at the risk of the new doses making me sick.

That level of outside authority is one that women who’ve grown up in a patriarchal society are already used to. We’ve had it enforced from birth that our wishes and agency are second to the men around us, second to our families, second to the comfort of our community, etc. Favor Hamilton’s story is rife with that conflict, even in instances unconnected with her mental health or sex work. From the other department’s coach in college who videotaped her breasts as she ran, with no negative consequences; to the coach who dictated her sex life after her marriage; to the spectators and competitors who claimed her main talent was her beauty; to her dad’s pushiness and embarrassment in response to her swimsuit calendar modeling, the list goes on and on.

If you look at bipolar people’s relationships as a push-and-pull between themselves and their effect on people around them, it’s unsurprising that having her bodily autonomy undermined so long led Favor Hamilton to challenge those around her to accept her as a sexual being with agency.

But this sense of herself as communal is evident in several of Favor Hamilton’s behaviors, such as her inability to turn down anyone requesting her time and labor as a celebrity. It’s also there in her idea that her achievements weren’t hers, but were her husband’s for what he sacrificed to further her career, or her family’s, particularly her brother’s after his suicide. When you factor in her family’s antipathy toward her speaking about depression and her brother’s death, it’s no wonder that the actions she took to gain something for herself were largely targeted at self-ownership. The eating disorder she had in college, the swimsuit calendar that enraged her dad so much, her disappointing collapse running in Sydney, even her breast reduction, were designed to preserve some part of her from public appraisal and criticism. Later on, she lobbied her husband for an open marriage, set sexual boundaries with the escorts she patronized, and finally became an escort herself. All these choices seem to have been aimed at blocking off parts of herself from the people around her.

She developed her sex work persona to emulate the best characteristics of someone she greatly admired, outspoken in all the ways she previously couldn’t be. That decision also felt organic to the triggers laid out in her upbringing and running career.

I particularly enjoyed Favor Hamilton’s insight on how similar sex work can be to the performative effort behind athletics—the fake smiling and the sense that one off day can make or break you. Favor Hamilton also depicts the physicality and purpose behind both jobs as coping mechanisms for dealing with bipolar. She describes her running as something that staved off the worst of her disease. Certainly my own stint stripping soothed my symptoms, much the same way Favor Hamilton’s running, and later her escorting, helped dampen some of hers.

As I read the memoir, I couldn’t help but contrast Favor Hamilton’s perceptions of the disorder with my own. Favor Hamilton writes,

I think the hardest part of my recovery has been looking back at my behavior that was so destructive to my marriage, my family, and myself, and finding a way to make sense of it as the illness working through me, not something I consciously chose myself.

That’s not something that’s universal among those living with bipolar disorder. Our coping mechanisms are different, and mine is the exact opposite: If I have reason to believe everything is in the disorder’s control, I tend to be far less active in countering its negative effects. My philosophy is that while I am living with the disorder, it still falls to me to control its most harmful effects. I think this difference in coping mechanism and perception gets to the gut of the controversy about whether Favor Hamilton adequately takes responsibility for her choices. In the memoir, she seems to insist: It’s the disorder, not me. Not my choice. Not at all.

For sex workers, this is a spiel we’ve all heard a million times: you don’t know what harm you’re doing to yourself, you’re better than this, just do the 12 Steps program or court-mandated yoga classes, just stop seeing clients, just be normal, stop calling this a choice when it’s pure exploitation. Just call yourself a victim.

Many of us only gain our power from saying, unequivocally, this is me, the good, the bad, and the ugly. It’s easy to want to demand the same from Favor Hamilton, to narrow our eyes when she insists it was just the illness and the medication driving her sex work, rather than a series of choices that she made, same as the rest of us.

It appears Favor Hamilton developed triggers associated with a lifetime of being unable to assert herself and simply own her body. And I got that pretty keenly. It’s something that most of the sex workers I’ve known have dealt with on some level, even those who aren’t struggling with a debilitating mental illness. Issues of agency and self-ownership are at the core of sex work, and Favor Hamilton had already been wrestling with them for years, through her athletics and her public persona.

Still, passages like this really didn’t sit well with me:

Being bipolar means being insatiable. The high of the mania is never high enough. There’s always a desire—a need—to push the high to the next level, in the same way that a drug addict constantly requires more and stronger drugs. For a person with bipolar disorder, risky behavior can be the best drug of all. And there are particular kinds of dangerous activities that feel better than others; sexually provocative behavior is near the top of the list. Also up there are spending large sums of money, and taking drugs, and drinking alcohol. In a way that someone without bipolar disorder may have difficulty understanding, there is no longer any voice of reason that can assess the potential negative consequences or stop the behavior. Much like a teenager with no impulse control, a person with bipolar disorder can only see the immediate positive outcome of feeding the high: it will feel good. Everything else—family, friends, employers, safety—falls by the wayside in pursuit of the high.

Favor Hamilton’s views hit a soft spot with me, as they play into narratives I was raised with that made me feel less powerful in my own dealings with my illness. These are models I consciously rejected as part of my self-care process. It made me worry about her presenting the disorder that way to her readership, knowing how hard I’ve worked to get away from the idea of being my disease’s puppet. My motto is “just because I’m manic doesn’t mean I’m out of control,” which is contrary to her description of bipolar manias—as “highs” to be “fed” with adrenaline-seeking or risky behavior, that can depreciate when that behavior is no longer dangerous enough.

The passages in Fast Girl actually related to Favor Hamilton’s sex work were surprisingly sparse. The sex work encompasses a bare handful of chapters, and those are the ones most heavily peppered with asides about the nature of bipolar. Favor Hamilton claims that the entirety of this time in her life was a bipolar mania. Most of the descriptions tend to be lurid, focusing on how much her clients liked her and where they fucked her, or the stuff they said to the woman running the escort agency about her. Aside from a few passages about her exhilaration doing the work and and her exhibitionism, there’s surprisingly little there that’s substantive. The focus of the book is on the way that her mental illness developed and played out through her athletic career, and how she coped with having her sex work exposed in the press.

A lot of Fast Girl read like an apology, a plea to be understood. This is especially understandable since the author still lives in the conservative Wisconsin circles she describes growing up in, is still with the man she was married to before her diagnosis, and still operates in the fairly conservative public eye. Given all this, her reading of her bipolar disorder makes sense, but parts of it definitely made me grit my teeth. It seemed a disservice to both the bipolar community and the sex work community.

I don’t think anyone’s going to be able to say for sure exactly what happened to Favor Hamilton. Even after reading Fast Girl, I still don’t think she’s been able to tell that story. At least, not while also trying to simultaneously contain the damage of being outed as a sex worker, win back the support of those who felt most hurt by her behavior, as well as pacify psychiatrists and a general public still inclined to consider sex work an act of self-harm.

Favor Hamilton’s truth is never going to come out cleanly; it’s going to be filtered through everyone else. It’s going to be told through the reporters whom she may have felt she had to play victim for to salvage her reputation, who cherry-pick that aspect of her story due to having preconceived notions of sex workers as fundamentally broken. It will be told through non-neurodivergent sex workers angry at how the framing of her story denies her any responsibility for her career choice, as this framing mirrors the stigma they deal with in their own lives. And it will be told through neurodivergent sex workers like me who might feel somewhat more secure in their choices, but who still question them every day, feeling a vague sense of guilt at playing into stereotypes about crazy whores.

Great review! Thanks so much for candor and for speaking about living with bipolar 🙂

Thank you for this. <3

[…] It’s been a hella crazy month. Lots of new titles up, including some ones that are wildly different than what you’ve seen from me thus far. But on top of that, I can now cross one thing off my bucket list: writing for Tits and Sass. […]

Really interesting connection there, between athletics and sex work. Reminds me of my own ruminations as to how I slipped into the erotic business. Before becoming an erotic masseuse I had danced ballet for 14 years, and I totally agree that the “performative effort” common to both performing arts and sex work makes it easy to transition from one into the other. Body work in general somehow conditions those performing it to obectify themselves over time, creating a mental distance between oneself and the body’s actions when performing for others, so that it becomes routine and almost natural to be putting the body to work for others. A good friend of mine who was also a sex worker, was also a professional ballerina before discovering sex work. After being valued and evaluated for how she presented her body for so many years, being successful at sex work was not a problem or in any way uncomfortable. The blocking mechanisms built up in the ballet world–learning to withstand the initial pain of being en pointe; learning to bury all negative emotions for the sake of maintaining grace, elegance and poise–are very useful for doing sex work. Blocking is not necessarily a psychologically “bad” thing…I think a lot of people in general use blocking mechanisms to get through life. I’ve come to view it as a trait that can be built up and transferred across different activities or professions, similar to perseverance.

[…] career, her stint escorting, her family life, and her struggle with bipolar disorder. After reviewing the book for Tits and Sass, contributor Katie de Long had a conversation with Favor Hamilton over e-mail about the New York […]

everyone’s individual experiences with bipolar disorder are just that (individual), plus i’m a civilian who’s got bipolar II with a lot of complicating *physical* factors, but that highlighted passage was very much not how *mine* feels.