The Gr8 Pole Deb8: PoleCon Edition

Three years ago, at this very time of year, this post came across my Tumblr dashboard. It was the first time I had seen anything like it and I was staggered.

Stripper tumblr (strumplr?) was outraged, and though responses began with the intent of being educational, they devolved quickly as the original poster, Kelly, blasted back with the same clueless defensiveness that most people demonstrate when told they’ve been thoughtlessly oppressive and insulting to another group of marginalized people.

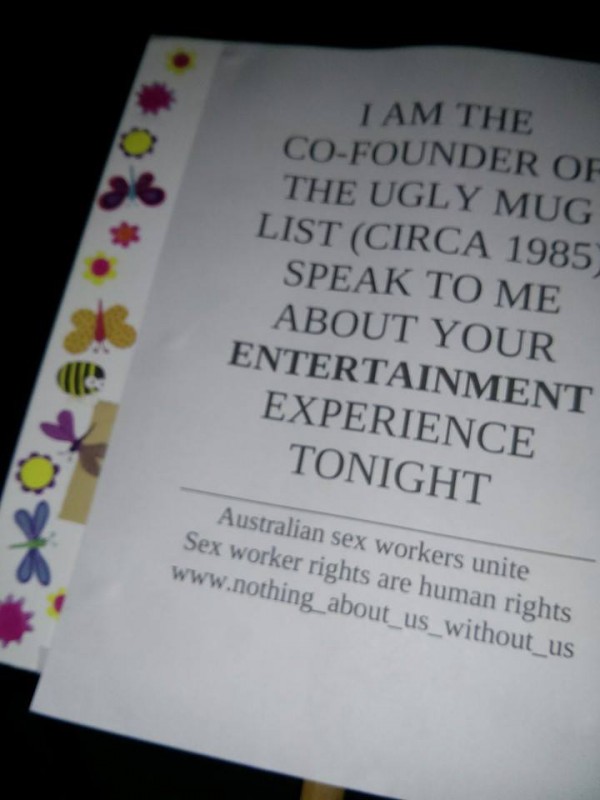

My response then is basically the same as my response now, although the years have honed it and solidified my personal feeling that hobbyists (non-in person sex workers) have no business being within feet of a pole. If you aren’t going to work fifteen-thirty hours a week in 7” lucite heels; having beer breath burped in your face; learning with each rotation how to do pole tricks, in front of a live audience; risking your position in grad school (“ethical conflict”); your ability to get an apartment (“but your income isn’t documented”); your ability to keep custody of your kids (“she’s a fucking whore who takes it off in front of people for money, she’s clearly an unfit mother,” never mind that that wasn’t a problem when she was giving you her money); then you have no business using us as a costume. You have no business pretending that the performance of labor that wrecks our lower discs and ribs, forcing us to suck in our bellies, point our toes, and arch our back to the point of pain, is somehow relevant to your sexuality. I can’t stop you, but that doesn’t make it right. We’re not your sexy stripper costume. If you can’t hack the labor, you don’t get the edgy whiff of transgression.

This was my first intro to the “#notastripper” phenomenon, or as I like to call and tag it, “#the gr8 pole deb8.”

It was not to be my last encounter with these people, not by a long shot. It wasn’t even my last encounter with Kelly, who refused to go away or even show any embarrassment and instead proceeded to insist that she “loves and respects strippers, but she’s not just some bitch with daddy issues shuffling around the pole.”

I mean, honestly. You parse that one. My life is too short.

“#Notastripper” spawned many articles, because what internet editor doesn’t love that combo of sex work and scantily clad women, especially when it means the lead image can be sexy? (I may have the only editors of an internet news/pop culture site who do not go for these things. Bless.) My personal favorite is by Alana Massey, Why is there an ongoing feud between strippers and pole dancers?

All the while pole hobbyists were writing articles and blog posts bemoaning the just truly baffling conflation of pole work with strippers, one woman even daring to say that she was getting stigmatized for her sexuality. Where to even begin!

In the past three years, however, I have never read anything as ignorant, uneducated, condescending, and blatantly offensive as I did this week, in a post leading up to this week’s International Pole Convention in Atlanta, Georgia.

In an open letter to her “Exotic Pole Dance Sisters” Nia Burks calls for them to take the stage this weekend mindful of those who came up with their fun extracurricular activity. All well and good, right? I felt like finally, an asshole pole hobbyist was taking my demand for them to minimize their asshole-ness seriously and acknowledging strippers. Righteous. But read on.

New sex worker writers often justify their sex work with respectability politics.

New sex worker writers often justify their sex work with respectability politics. This is an edited version of

This is an edited version of