More Than Silence: Tjhisha Ball, Angelia Mangum, and the Erasure of Black Sex Workers

Tjhisha Ball and Angelia Mangum: Two names you should know but probably don’t. Tjhisha Ball and Angelia Mangum were 19 and 18 years old, respectively, two young women who were brutally murdered on September 18th. Their bodies were found in Duval County, Florida, reportedly thrown off an overpass, by passerby in the wee hours of the morning. Little has been said about the murder of both of these young women, and what has been said either glosses over or luridly magnifies one very important factor in this case: Tjhisha and Angelia worked as exotic dancers.

Over at PostRacialComments on Tumblr, the blog not only redacted the information about Mangum and Ball working as dancers, but proceeded to break down for readers questioning its motives why they would not include, comment, or discuss the girls’ work or the criminalization of the girls by the few media outlets to highlight the story of their murder.

In “Black Girls Murdered (But Do YOU Care)” from Ebony Magazine, Senior Digital Editor Jamilah Lemieux says, “Someone(s) apparently murdered two women and left their bodies on the side of the road for the world to see. We shouldn’t need for them to have been “good girls”—or White girls, or, perhaps good White girls—for this to be cause for national concern. There is a killer, or killers, on the loose.”

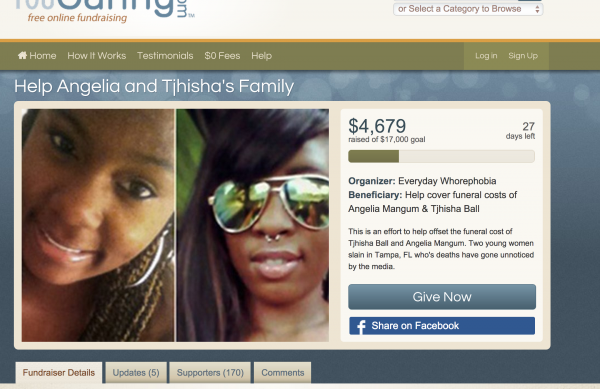

We are just about $150 away from having $4,000 to help bury #TjhishaAndAngelia. Thank u. Thank u! Pls keep sharing! http://t.co/JM3Cq8LLIb

— Rap Game Rahab, doe (@_peech) September 27, 2014

In “Rest in Peace: Angelia Mangum and Tjhisha Ball” from GradientLair, owner, activist, and blogger Trudy writes, “As I’ve stated before, Black criminals are treated like monsters. Black victims are treated like criminals. This further complicates, in addition to the dehumanization and criminalization of Black bodies, because they are Black women. Black women regularly go missing and at times are killed; our stories are underreported or shaped as “criminal” even when we are victims.”

While both pieces were necessary and both began to address the case of Tjhisha and Angelia’s murders, they are certainly the anomaly in terms of the majority of the coverage. Even in the case of “Black Girls Murdered,” a mostly positive portrayal, I thought to myself, “Why are we not acknowledging their work? Why are we pretending their work doesn’t matter? Why is their work becoming the elephant in the room?” I walked away from most articles I read feeling both shameful and shamed, as if they were written to say, “News reports say they were exotic dancers, quick, let’s fight to erase that so the girls can appear deserving of our sorrow and rage.”

At Salon, writer Ian Blair penned “Grisly Murder Ignored: How We Failed Angelia Mangum and Tjhisha Ball” and went so far as to completely erase input given on this case by sex workers. Not only did Blair not reach out to any sex workers, he neglected to quote any of a wide pool of us who have been posting regularly about these girls for nearly a week straight. Blair’s piece barely nods to and briefly namechecks “the sex work activist community,” with no mention of the YouCaring fundraiser Melissandre (@MeliMachiavelli) and I set up to fund the victims’ funerals. The piece reads as if Blair simply copied and pasted information he read online and didn’t bother to interview a single person for his article. There is no acknowledgement that much of his information came directly from current and former sex workers on Twitter. Salon’s writer fails to point out that neither Ball or Mangum’s families have enough money to bury the girls and the YouCaring fundraiser exists solely to help them with this endeavor. Blair prattles on, without much reference to Tjhisha Ball and Angelia Mangum themselves (the subjects of said “failure” on “our” collective part), instead devoting most of his column space to regurgitating words of well known and more respected Black people; quoting Ta-nehisi Coates at length; discussing Ferguson; Mike Brown; #IfTheyGunnedMeDown; Daniel Holtzclaw; Marlene Pinnock, and seemingly anything other than what the Salon write-up ostensibly set out to address: two beautiful young women who were brutally murdered and who also happened to work as strippers. This offering from Blair also casually ignores the reports that each of Daniel Holtzclaw’s alleged victims, save the last woman he is accused of having victimized, were also either sex workers, drug users, or both.

Black sex workers are important. #TjhishaAndAngelia http://t.co/KN8ILueS8T — Skelewhore (@desiderata_x) September 22, 2014

In fact, in the cases of Tjhisha Ball and Angelia Mangum, as in the case of Daniel Holtzclaw and his alleged victims, the idea of sex work as an important factor in the crime continues to be obscured by other supposedly more important issues, watered down to nothing in order to be considered palatable to sensitive audiences. The few conversations I’ve seen on Twitter, Tumblr, and the occasional news articles and blogs focus only on the collective (non)reactions of people when a Black woman is the victim of violent crime. I do not want to take anything away from that analysis. I know it’s absolutely true: Black women are the least and the last in line for anger, rage, justice, pity, sympathy, and empathy.

@PhilOfDreams said it wonderfully on his Twitter feed:

“murder of a white woman: there must be an investigation.

murder of a black woman: there must be an explanation.”

Black women are upset, we are incredibly sad, we are begging to be cared for, and we have a right to feel this way. We are completely correct in our steadfast refusal to simply disappear into the ether when we are violated, when our lives are snuffed out. We are justified in our anguish and in our anger. We are righteous in this, and I am not here to take away from it. I am here standing with my sisters and speaking out too. We are the most spotless of lambs, sinless in our desire to simply be seen as just as important as anyone else. But, what I am also here to say is this: in the midst of the tangible and thickening silence from what could arguably be called one of the most vocal corners of twitter, Black Feminist Twitter, and even Feminist Twitter as a whole; in the midst of the silence from virtually everyone and everywhere: where is the outrage for two teenage girls who were brutally murdered? Is the outrage lacking because of their race? Definitely. Is it non-existent because of their reported interactions with law enforcement? Absolutely. But it is also lacking because they were reported as working as exotic dancers. This cannot be denied. It is unfair and unethical to say anything different.