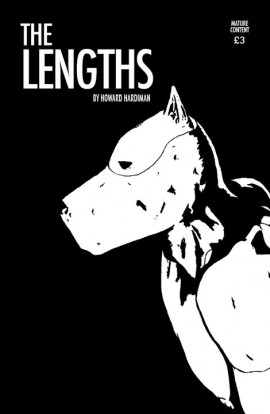

The Lengths (2013)

When did I last read a novel about gay male escorts that didn’t make me want to set the world on fire with rage? It was probably Rupert Everett’s Hello, Darling, Are You Working?, one of the sex workers’ rights advocate/actor’s less well-known works. But also I read that book years ago, so long ago in fact that I don’t really even remember too much about it, beyond that it wasn’t completely maddening.

I haven’t done a study or anything, but it seems that rent boys feature in memoirs a lot more than they feature in novels. (The most recent example I know of was self-published by gay porn star Christopher Daniels in November; I haven’t read it.) But even some of the fictional works—Everett’s among them—are at least somewhat autobiographical. Howard Hardiman, author of eight-issue comic The Lengths, fits into that category. In an interview with The New Statesman he says he “did a bit of sex work” with some of his escort friends, and it’s evident that he sympathizes with his characters. The Lengths is fiction, but in addition to (presumably) drawing on his own experiences Hardiman clearly did a lot of research, interviewing London’s male sex workers as he assembled the story of a wayward dog named Eddie.

Yes, Eddie is a dog. I think he’s a bull terrier?

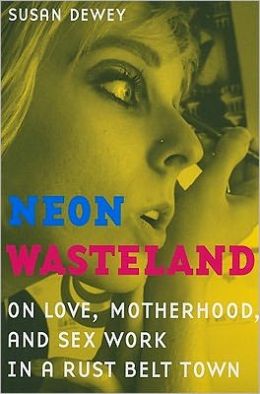

Susan Dewey conducted fieldwork for her academic study at a strip club she calls “Vixens” in a town she calls “Sparksburgh” in the post-industrial economy in upstate New York. She describes interacting with approximately 50 dancers but focuses on a few: Angel, Chantelle, Cinnamon, Diamond, and Star. Some names were changed, but these pseudonyms will sound familiar to anyone who has spent time in a club. The run-down club offers entertainment for working class people in an area with high unemployment. The club is not glamorous but is perceived as the best opportunity in a place of few options, including a few other bars with exotic dancers.

Susan Dewey conducted fieldwork for her academic study at a strip club she calls “Vixens” in a town she calls “Sparksburgh” in the post-industrial economy in upstate New York. She describes interacting with approximately 50 dancers but focuses on a few: Angel, Chantelle, Cinnamon, Diamond, and Star. Some names were changed, but these pseudonyms will sound familiar to anyone who has spent time in a club. The run-down club offers entertainment for working class people in an area with high unemployment. The club is not glamorous but is perceived as the best opportunity in a place of few options, including a few other bars with exotic dancers.