On Surviving Sex Work

This post was removed at the author’s request.

This post was removed at the author’s request.

One of the most disappointing aspects of this story has been AIM’s response. While quick to defend their own organization, calling themselves victims of a security breach comparable to the hacking of the Pentagon and virulently noting that not all the information on the site came from them specifically, there has been no discernible effort made to notify the victims that their information has been made public. […] Sex workers want a medical center tailored to the specific needs of the sex industry, including protection of anonymity.”

Read the entire press release here.

I was a scab on Wednesday during the Women’s Strike. Too broke and disorganized as usual, still messily addicted, I ended up having to see a client. And sure, I wore red, and I limited my shopping to the South Asian woman-owned convenience store down the street, and I tried to allow the organizers’ reassurance to poor women that donning my ratty old Red Sox t-shirt would suffice as participation to soothe me. But I felt the usual radical white guilt I always feel on similar occasions like Buy Nothing Day, shame at the fact that I wasn’t part of this leftist ritual.

And I was irritated with myself for being ashamed. I knew this strike couldn’t realistically rely on all women joining it. Even if we were all ideologically inclined the same way, even if we could all afford to take the day off work, women aren’t all one class of worker, and that complicates things. The many schools forced to close anticipating teachers not coming in demonstrated that the action had real economic impact. But ultimately, its effect was symbolic, meant to show how much everyone relied on women’s paid and unpaid labor. I did wonder skeptically how many women employers had actually given their nannies and domestic workers a paid day off as organizers suggested, when usually, that domestic work is what allowed these women employers the time for political action in the first place. But I had to admit that the organizers had thought of multiple ways for women in many different economic circumstances to show solidarity.

Still, I was distrustful of these strike organizers, some of the same women behind the Women’s March on Washington the day after the inauguration, the people who erased pro-sex workers’ rights language from their agenda document. Only ex-sex worker and acclaimed writer and editor Janet Mock’s public protest at the omission compelled them to add it back. But the pro-sex worker statement, once reinstated, had to keep company with the anti-trafficking discourse that had been written in in its stead. And how comfortable were young trans sex working women, like the teenaged Janet Mock was, supposed to be faced with a cadre of marchers who thought that wearing hot pink plush vagina hats as a symbol of their womanhood was an excellent idea? The pervasive transmisogyny and anti-sex worker sentiments within liberal feminism can be subtle in their manifestation, but it still feels like they’re always there.

But sex work was included in the strike organizers’ February announcement of the action in the Guardian as one example of the gendered labor women were striking from. (Maybe we have prison abolitionist sex worker ally Angela Davis, one of the many co-authors of the statement, to thank for that.) And this time, with a new coalition called the International Women’s Strike USA joining the March organizers in drafting it, sex workers were also included in the call for labor rights on the U.S. Women’s Strike platform. Trans women were acknowledged in that agenda multiple times as well. Many sex workers’ rights organizations around the world, from the U.S. PROS Collective to Ammar, had announced their intention to join the action. So why did I still feel bitter?

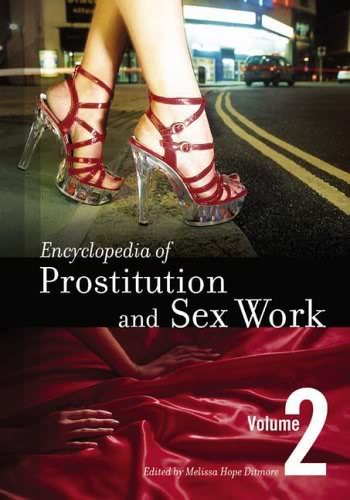

Dr. Melissa Ditmore is one of the sex workers’ rights movement’s most cherished academics. For twelve years, she has worked as a freelance research consultant, with an impressive list of clients that includes AIDS Fonds Netherland, UNAIDS, The Sex Workers’ Rights Project at the Urban Justice Center, and The Global Network of Sex Work Projects (NSWP). Her work has focused not only on sex workers’ rights, but also those of similarly marginalized groups like migrant workers and drug users. She edited the groundbreaking anthology Sex Work Matters and the history Prostitution and Sex Work, headed seminal research like the Sex Workers’ Project’s “Behind Closed Doors,” and she’s written regular pro-sex workers’ rights pieces for RH Reality Check and The Guardian. The project she’s most known for, though, is the gargantuan effort that produced Encyclopedia of Prostitution and Sex Work, a two volume labor of love that has already become a movement classic since its publication in 2006.

Dr. Melissa Ditmore is one of the sex workers’ rights movement’s most cherished academics. For twelve years, she has worked as a freelance research consultant, with an impressive list of clients that includes AIDS Fonds Netherland, UNAIDS, The Sex Workers’ Rights Project at the Urban Justice Center, and The Global Network of Sex Work Projects (NSWP). Her work has focused not only on sex workers’ rights, but also those of similarly marginalized groups like migrant workers and drug users. She edited the groundbreaking anthology Sex Work Matters and the history Prostitution and Sex Work, headed seminal research like the Sex Workers’ Project’s “Behind Closed Doors,” and she’s written regular pro-sex workers’ rights pieces for RH Reality Check and The Guardian. The project she’s most known for, though, is the gargantuan effort that produced Encyclopedia of Prostitution and Sex Work, a two volume labor of love that has already become a movement classic since its publication in 2006.

Jessica Land: How did you come to edit the Encyclopedia of Prostitution and Sex Work? It’s such an important work for both academics and sex workers’ rights activists, but buying the Encyclopedia isn’t feasible for many people due to price. For this reason, I’m almost giddy every time I find the volumes in a library. Is the Encyclopedia widely available in library settings?

Melissa Ditmore: I am always thrilled to see the Encyclopedia in libraries and in their catalogs! As you say, it’s an expensive book, as are most reference works. Reference books are intended for libraries, so this is how most people will get access to it. It had a second printing, so it sold well, mostly to university libraries and public libraries. Jorge Luis Borges wrote a story about a fictional encyclopedia that influences history. What I want for the Encyclopedia is for some of the history to be easily found and remembered, and being in libraries is key to that.

The publisher wanted to do this, and contacted Priscilla Alexander, who co-edited Sex Work, about taking it on. She was interested and asked me to work on it with her. As we worked on the proposal, it became clear that her job was too demanding for her to be able to do both her job and such a large editing project. And it was a large project: Priscilla helped with the initial list of entries, and there are 342 entries by 179 authors. Priscilla remained on the advisory board and was very helpful throughout.

Your vast contributions to sex work research have served the interests of sex workers’ rights activists for twelve years. You’ve been involved with a wide range of organizations, from the Global Network of Sex Work Projects (NSWP) to PONY (Prostitutes of New York.)What are some of the harder things you have confronted?

PONY once received an inquiry from a female law enforcement officer in the American south, and I followed up. This officer told me that a well-connected officer she worked with was abusing his power to commit extreme violence. She said that he used his badge to force women into his car, and then he would take them far away from the place they met. She believed he had murdered women, and she feared for herself if she brought attention to it, but could not live with staying quiet either. While PONY had helped other people with referrals to attorneys and even introduced them to someone who successfully pressed charges against a serial rapist in NYC, PONY had nothing to offer her in her region, and this guy may have murdered again. She only got to vent, and I hope she found the courage to report her violent co-worker to the feds, as she made it sound like the equivalent of internal affairs there would not be helpful or concerned. That was deeply distressing for both of us.

Readers of Tits and Sass know that murders of sex workers are all too common and often happen without diligent investigation, as documented in the recent book Lost Girls.

Since I began writing this piece, both Scarlet Alliance and SWOP NSW have issued an apology to migrant sex workers for their part in the SEXHUM research. This is an unprecedented move in the right direction for peer organizations. I hope that there will be more attempts in the future to empower migrants and POC, including Aboriginal sex workers, toward self-advocacy. I also hope that in the future, such a statement and its denunciation of non-peer-led research will be initiated by organizations without the need for heavy internal and external pressure from migrant sex workers first. Indeed, I hope that no statements like this are necessary in the future because this complicity with typically unethical outsider-led research will cease to occur in the first place.

As sex worker activists we love pointing fingers at the anti-trafficking industry, whorephobic art and media, and researchers with save-the-whore complexes. Yet, the sex worker activist movement itself is similarly stigmatizing towards migrant POC sex workers. Our movement has promoted the New Zealand decriminalization model for decades without being critical of New Zealand’s criminalization of migrant workers. The global sex workers’ rights movement heralds decriminalization at all costs, while often overlooking the racism involved in its partial implementation. The argument is that decriminalization of sex work will end stigma and benefit all workers equally. However, POC migrant sex workers (PMSW) still experience stigma, raids, and racism within the purported decriminalized sex worker heavens of New South Wales, Australia and New Zealand.