Carol Leigh, aka Scarlot Harlot, was the first sex workers’ rights movement celebrity I ever met. I’d been escorting for only a few months when she came to speak in my area, and I identified deeply with her writing in my dogeared copy of the 1980s edition of Sex Work. I was struck immediately by her spaced out, comforting voice, her self-deprecating yet confrontational humor, and her political conviction. My coworkers and I enjoyed how frank and matter-of-fact she was with us, dishing about clients like we were already old friends. Carol is the kind of person one needs in every movement: able to connect with anyone and everyone, able to bring people together easily. No wonder she’s been so effective in her pioneering role as one of the first artist activists of the sex workers’ rights movement.

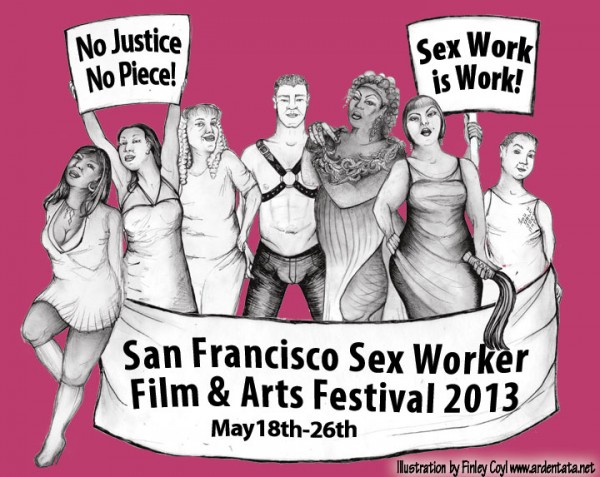

I caught up with Carol while she was working on two events, the upcoming Desiree Alliance Conference in Las Vegas and the 8th Biennial San Francisco Sex Worker Film and Arts Festival, and yet she still put aside time to do this interview with me.

One of the things you’re most renowned for is coining the term “sex work” in the late 1970s. How well do you think the term has held up as a way to describe our work and unite us politically?

When I think of the term and concept of “sex work,” I think of how it has empowered our activism through international use. This global proliferation of the term was largely due to the work of my mentor, Priscilla Alexander, who worked at WHO (World Health Organization) in the 80s. “Sex work” is particularly powerful as it was the first term that referred to this act without euphemism. The term “sex work” implies a rights advocacy.

At the same time some issues have come up with the use of this term.

I have heard from some quarters that sex work implies consensuality. At first I strongly resisted that notion, from the perspective that if sex work is basically work, then, in general, all work can be forced. Someone doing factory work, domestic work, etc. can be forced. (I use the term “forced” in a very general way as forced labor is part of a continuum of labor abuses.) It has been very basic in sex work advocacy to emphasize that prostitution is work, as opposed to an expression of one’s personal deviance, or a form of rape.

I often hear sex workers explain that they are not trafficked victims, but rather workers. I want to remind people, as we hold the reins of our options, that when force and choice are seen as a dualism, it obscures class and other divisions. Economic factors greatly impact one’s choices. In response to accusations about prostitution defined as rape per se, sex workers are moved to defend our work as “choice,” when we mean relative choice or choice among certain options. It’s just another typical case in which our message can’t come forth with the clarity we need and want, because we are in such a tight corner, due to laws and stigma. The term “sex work” can fall prey to dualistic thinking when one claims that by definition “sex work” implies consent. This is a long discussion and I haven’t seen much written about this. I look forward to the ongoing work of developing political philosophy based on our experiences of sex work. There is a lot we can learn from each other about discrimination, sex, minority rights, race, class, and survival.

As an early pioneer in our movement yourself, and the project director of the Center for Sex and Culture’s Sex Worker Media library, you have a uniquely knowledgeable perspective on sex worker history. What’s the most valuable lesson we can learn from our past?

The history of sex worker activism is so young. I guess I would barely characterize us as having a past. I’m only speaking to issues in the U.S., as my expertise is not global. We can trace ourselves back to organizations like COYOTE and US PROStitutes Collective and learn about the nature of their campaigns. Sex worker activists in the U.S. could (and probably do) read Judith Walkowitz and Ruth Rosen, et al and understand the factors that lead up to the current criminalization, and the trends in legal responses to white slavery panic that resulted in this current extreme criminalization of prostitution. We could study the development of U.S. and international sex worker rights charters and clarify our issues.

Our movements in the U.S. (and internationally) have grown exponentially while at the same time laws and enforcement become harsher. The formation of SWOP (Sex Workers’ Outreach Project), a national sex worker rights organization founded by Robyn Few and Stacey Swimme, was a major step forward and provides a needed organizing structure. This helps us enormously as we work with new strategies — challenges to prostitution laws based on constitutional issues like in Canada and developing self-regulatory models like DMSC (Durbar Mahila Samanwaya Committee) in India and launching legislation and ballot initiatives, to name a few.

It seems to me that in the earliest days of the movement, much of the emphasis was on political philosophy, but the last couple of decades I have seen an emphasis on community building. Here, I think we can learn from the efforts of movement founders. Our early charters (documented in Vindication of The Rights of Whores) laid the the groundwork, in terms of concepts about paths to justice for sex workers, regulatory models, etc. But much more work needs to be done in this direction.

We need to learn how to develop past the 70s movement based on middle class feminism/queer activism to a movement that is based in the representation and leadership of sex workers from all communities, strata, and circumstances. Maybe after years of feminism and other movements that were largely dissociated from issues of class and race, things will shift.

What’s your current analysis of trafficking hysteria?

Any challenge to the mainstream specter of “human trafficking” categorizes one as a miscreant, sort of like being a modern day Communist. So much so that every mention of trafficking must be couched among words like “heinous” which, combined with “trafficking,” renders over 4 million pages when paired in a Google search (more than “murder,” “child abuse,” “terrorism,” or “torture.”) So much so that statements challenging any aspect of the the discourse on trafficking must be preceded by an oath of loyalty to the cause. There’s some sort of implication in the requirement to swear allegiance, that people are not sufficiently opposed to brutality. Who is FOR forced slavery and torture? Ultimately one must prove one’s opposition by signing on to the most desperate strong arm methods. So that’s where the concern becomes a panic, and sex workers and all the other usual targets of government repression and state violence become collateral damage. I’ve been critiquing anti-trafficking campaigns and policies since the mid nineties, while collecting material for my film, Collateral Damage: Sex Workers and The Anti-Trafficking Campaigns.

Government responses to trafficking, like the white slavery discourse in the last centuries, are historically problematic and counterproductive. Activist organizations like Aim for Human Rights promote impact assessments to unravel the statist anti-immigrant solutions, the increased surveillance and criminalization (of the poor, sex workers, young people, people of color, and immigrants) that accompanies anti-trafficking policies. But the momentum of the anti-trafficking discourse easily overtakes any resistance and activists who challenge the prison-industrial complex upon which this framework is built are buried in an avalanche of panic and punitive legislation such as California’s Prop 35 and Nevada’s proposed AB67.

The contemporary trafficking ideology is a recycled version of the 19th century views of female sexuality, purity, and corruption of innocence, which were very much a part of the white slavery discourse. The imagery and content of anti-trafficking campaigns largely demonstrate how society feels about sex: that sex is dangerous and women mostly suffer from sex.

At the same time, the state is focused on controlling borders and controlling its populace with sexual control as a prominent strategy. As Ann Jordan explained, at “From Prosecution to Empowerment“, in anti-trafficking policy, suffering that happens in conjunction with crossing borders is privileged over forced labor in general. This distracts from the abusive labor practices on which the state relies.

To pathologize migrants, claiming they are forced, erases the nuances of migration and shifts society’s focus away from economic inequities often at the root of exploitation in migration to that convenient focus on sex and sexual fear. Of course as a sex worker, I think about sexual control as a form or means of social control quite a bit. People of marginalized sexualities or engaging in marginal sexual practices will be most at risk of state interference, coercion, and violence.

I have come to think or rather, hope, based on the last cycle of the white slavery moral panic of the 19th and early 20th centuries, that this framework and relentless characterization of ALL sex workers as slaves and victims exhausts itself…eventually. Ultimately, I believe (well, “hope” might be more accurate) that society reaches its fill of this view of the female sexual experience and loses its blindness to the hypocrisy involved. Ultimately, people open their eyes to the evidence that rescue efforts actually harm vulnerable sex workers, that repressive laws such as criminalization of prostitution cause harm, that economic injustice and discrimination is at the root of forced and abuse of labor in general. It’s pretty simple. With that in mind, my personal strategy is to document the contemporary history of this cycle for the future. As a sex worker and sex worker’s rights activist, I feel it’s my duty to use the unique perspective I possess to correct the misinformation that the anti-trafficking discourse spreads.

Some of the most important work on this subject is by Elizabeth Bernstein as in included at the Interdisciplinary Project On Human Trafficking. I particularly want to direct attention to The Sexual Politics of the “New Abolitionism” and Militarized Humanitarianism Meets Carceral Feminism.

You write in the 1980s Sex Work anthology that “the suffragettes, our foremothers” helped criminalize prostitution to start with. With so many whorephobic, transphobic, and classist high profile feminists speaking for us out there, I feel like I’m hanging on to feminism by my fingernails, while many of my fellow sex workers have simply given up on it in disgust. How do we keep our faith in feminism and move to reclaim it?

I would say that myself and ask that question, only to add that at nearly 62, I am not concerned with a definition of my precise relationship to feminism. I am completely reconciled to the idea that the 20th century waves of feminism in the US were rooted in middle class priorities. That said, it did break my heart this year when Gloria Steinem and Ruchira Gupta were celebrated in that documentary at the same time that they were showing up in India, undermining the sex worker run organizations there, by denouncing them as being in league with traffickers and demanding that their funding be withdrawn. But I am tough. I can deal very well with the fact feminism and my own political background has been steeped in middle class presumptions and a wide range of gender, class, and race discriminations. I don’t need to feel that feminism is more than a helpful analysis for individuals specifically seeking more political and social power for women, all women, including right wing fundamentalist women, although they certainly were dragged into the 20th century version kicking and screaming. Perhaps it was a double edged sword, so that as middle class women ascended, class divisions became even more entrenched, going unchallenged in what was supposed to be an expressions of egalitarianism and social justice. Now that I am addressing it, I notice that I’ve finally dropped that nostalgic longing for what feminism should have been.

Many sex workers participate in political performance art now, but you were the innovator, with your raw, bawdy, comic performances, like the protest in which you carried a sign saying you’d have sex with someone for a dollar. Can you tell us why you chose performance art as the medium in which to express your ideas about sex work?

I moved to San Francisco to be Shirley Temple, to be one of the demimondaine. I wandered into prostitution as I was trying to survive outside the 40-hour-work-week-marriage-and-motherhood framework. So, the art and performance came first, the message later. My persona, Scarlot Harlot, and my material were all about “coming out” as a sex worker. As a child of the 60s, political activism was always the center of my life. As a feminist, I learned that women’s contributions were censored in our societies. That certainly applied to prostitutes! I knew the first day of work at the Hong Kong massage parlor on O’Farrell Street that the subject of prostitution would be the center of my life. Journaling was my initial medium as a writer, and so it made sense that my material would be my life. I figured I would be like a prostitute version of Hemingway.

Why do you think things like The Sex Workers’ Art Show are so effective?

Sex worker artists humanize this mysterious part of life, and expose the general public and our own communities to the nuances and diversity of sex workers’ lives and familiarize people with our struggles against stigma, criminalization, and violence. There are so many myths about sex workers that serve as some sort of proof that we are less than others, that we are damaged goods, that our thoughts are mostly delusions, false consciousness. Also, we are somehow presented as monolithic, whether it is in the image of the exclusive call girl, the addict, the street worker, or the trafficked victim. The images are contrasting, but they all obscure our humanity and diversity. The Sex Worker Art Show Tour presented a wide range of artists, and communicated wide differences in the ways individual artists with experience as sex workers saw their work and the world.

You’ve been creating video art for decades about sex workers’ rights issues, and you were the founder of the San Francisco Sex Worker Film and Arts Festival, now on its 8th run. Why is film important to the movement?

The San Francisco Sex Worker Film and Arts Festival was launched in 1999. Now our small team includes co-producer Erica Fabulous and movie curator, Laure McElroy. I was originally inspired by a sex worker made movie, A Gun For Jennifer by Deborah Twiss and Todd Morris. It was an ultra violent movie about strippers organized to wreak vengeful havoc on rapists. Why is film important to the movement? First of all, whore images in cinema are such a major part of the lexicon of information and cultural attitudes about prostitution. Since we are underground populations, people may not relate to sex workers in their daily lives. Art, literature and now film fills in the gaps. Second, sex workers are a major party of “sinema” as porn actors and producers. This generation of pornographers has been in the forefront of new modes in sexual representation with work from Nenna Joiner, Madison Young, Courtney Trouble and Jiz Lee, in developing women and trans* people’s points of view in erotic film.

And as video becomes one of the primary tool of activists in general, maybe sex workers are particularly prepared, motivated and inspired to create exciting new activist work. Some of the best recent work I have seen has come from the extensive collection from APNSW (Asia Pacific Network of Sex Workers). One of my particular favorites is to the tune of a Lady Gaga song, called Bad Rehab “…about the real issues for sex workers who are forced into rehabilitation centres in South East Asia- and the anti-trafficking “rescue industry” that has sprung up, and campaigns for laws and systems that restrict sex workers and promote further violence against them.” Another recent favorite is Last Rescue in Siam by EMpower in Thailand. Inspired by silent movies, it mocks the tactics of the rescuers and celebrates the humor and endurance of sex workers.

fuck yes! amazing interview! It touched on some very important issues. <3 this

Thank you!

Everything about this is perfect. I want to be Carol Leigh when I grow up.

You’re not alone in that sentiment. Thanks!

Yes! Anyone who aspires to be the prostitute Hemingway is an inspiring person indeed!

[…] Caty Simon of Tits and Sass continues a string of good interviews, this time with veteran activist Carol Leigh (AKA Scarlot Harlot), originator of the term “sex worker”. Carol speaks about the growth of activism, trafficking hysteria, neofeminism and whore art. […]

[…] check also this out! a smart Interview with Carol Leigh […]

[…] https://titsandsass.com/activist-spotlightcarol-leigh-on-sex-worker-sinema-and-challenging-the-anti-t… […]

[…] asked Carol Leigh in an interview last year how we can reclaim feminism from the trend toward sex worker exclusionary reactionary feminism, […]

[…] have the genre of representation that has been carefully encouraged by people like the incomparable Carol Leigh, and I am always keen to make films that speak to the sex worker community, but I have been working […]

[…] elder sex worker activist Carol Leigh was prescient when she told TAS in 2013, “We need to learn how to develop past the 70s movement based on middle class feminism/queer […]